Curse of the Ring: Das Rheingold

Richard Wagner began his monumental cycle of operas Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) in 1848, in the wake of the Age of Enlightenment. Reason, religious tolerance and the primacy of the individual are on the rise, and the influences of monarchy and church are weakening. The four operas that comprise the Ring cycle reflect the times, as they give us the end of the Age of the Gods and the beginning of the Age of Humans.

To get an idea of how revolutionary the Ring Cycle was, opera in the mid-1800s was dominated by the Bel Canto style—beautiful singing, with text that at times seemed incidental. Wagner believed that there was an imbalance between music and text, and he rejected the Bel Canto model in his 1851 book Opera and Drama. Drawing inspiration from the Greek model of theater as a sacred ritual, Wagner envisioned a theatrical experience that would change the listener, not just entertain them: a “Gesamkunstwerk” or “Total Artwork” that united multiple art forms into a cohesive whole. The Ring Cycle was to be a myth enacted through ritual to forge a national identity of shared values and ideals, ennobling the participants through the purging of fear and pity. This was meant to transform the listener through secular ritual, not merely give them pretty songs to listen to. There is magical power in a rite, but not in a show.

To accomplish his visionary goal, Wagner went back to Norse mythology. Wotan, Loki, Freia. A world of gods, goddesses, giants, dwarves, magic objects, enchantments, and curses. These are not just characters, though. As participants in the ritual, we are meant to identify with the gods and goddesses as we would with any myth. We are called upon to read ourselves into the text. Wagner raises some deep psychological issues (he’s as much Ibsen as Aeschylus) and poses this question to us: “Is this me? And if so, what do I do about it?”

Das Rheingold is the first of the four operas in the Cycle, an introduction to its characters and themes. Among the conflicts Wagner examines are power versus love, civilization versus barbarism, order by law versus order by force, and what happens to the world when you have the unholy union of corrupt leaders and a complicit society.

At the heart of the story is a golden Ring of Power, a symbol that extends back to Plato (The Ring of Gyges), through Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and on to H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man. The ring extends all-encompassing power upon its owner, with the caveat that in order to possess the ring, one must first totally renounce love. As George Bernard Shaw—one of Wagner’s great champions—points out, thousands of us do that every day. And while we may persuade ourselves that we wouldn’t go THAT far, it’s a reminder that power is purchased at the expense of communion, and every step up the ladder is a step away from fellowship and intimacy.

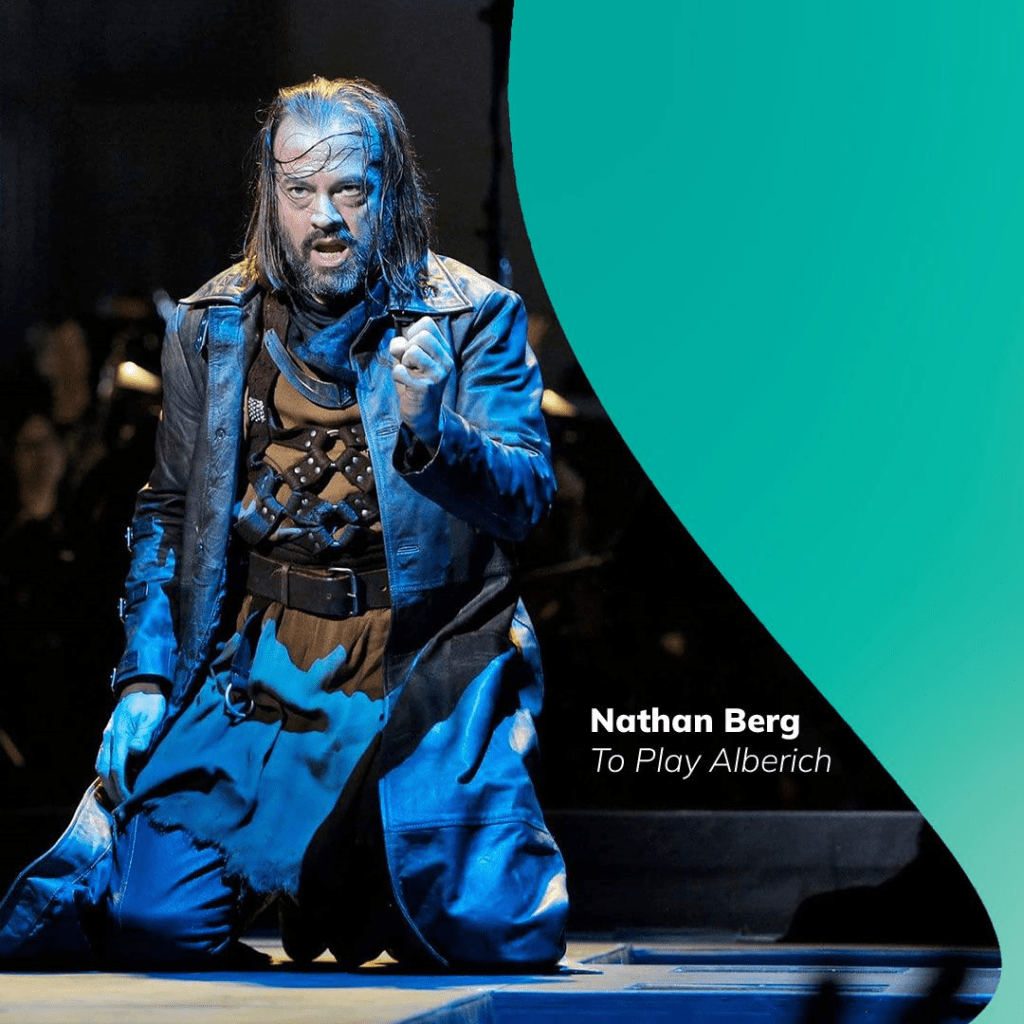

The Ring winds up on the finger of Alberich, the Nibelung of the title. Nibelung is equivalent to “dwarf” and you would be fine interpreting that as placing ultimate power in the worst hands imaginable. This comes to the attention of Wotan, the ambitious, amoral and corruptible King of the Norse Gods. He represents authority and order, a rule based on law and contracts, but he is in power and hungry to stay there.

In addition, Wotan has made a Very Stupid Promise. He contracted with the giants Fasolt and Fafner that if they built him a castle, they could have his sister-in-law Freia, the goddess of youth and beauty, as their wife. A couple of points: 1) Wotan MUST keep this agreement, or he loses his power and the gods fall, and 2) bartering away your sister-in-law for a home is NOT good marriage practice.

So, Wotan decides to steal the ring from Alberich and offer it to the giants in place of Freia. And 20 operatic hours later, the castle is in ruins and the gods are either dead or dying.

Meanwhile, we are left with a few questions: Would we be moral if there were no repercussions to immorality? Do we ever exchange love for power? Would we break the law and sacrifice our reputation for power? Do we want rule by law or rule by force? Does the unceasing quest for power destroy our capacity to believe in a just society? Is it true that might makes right?

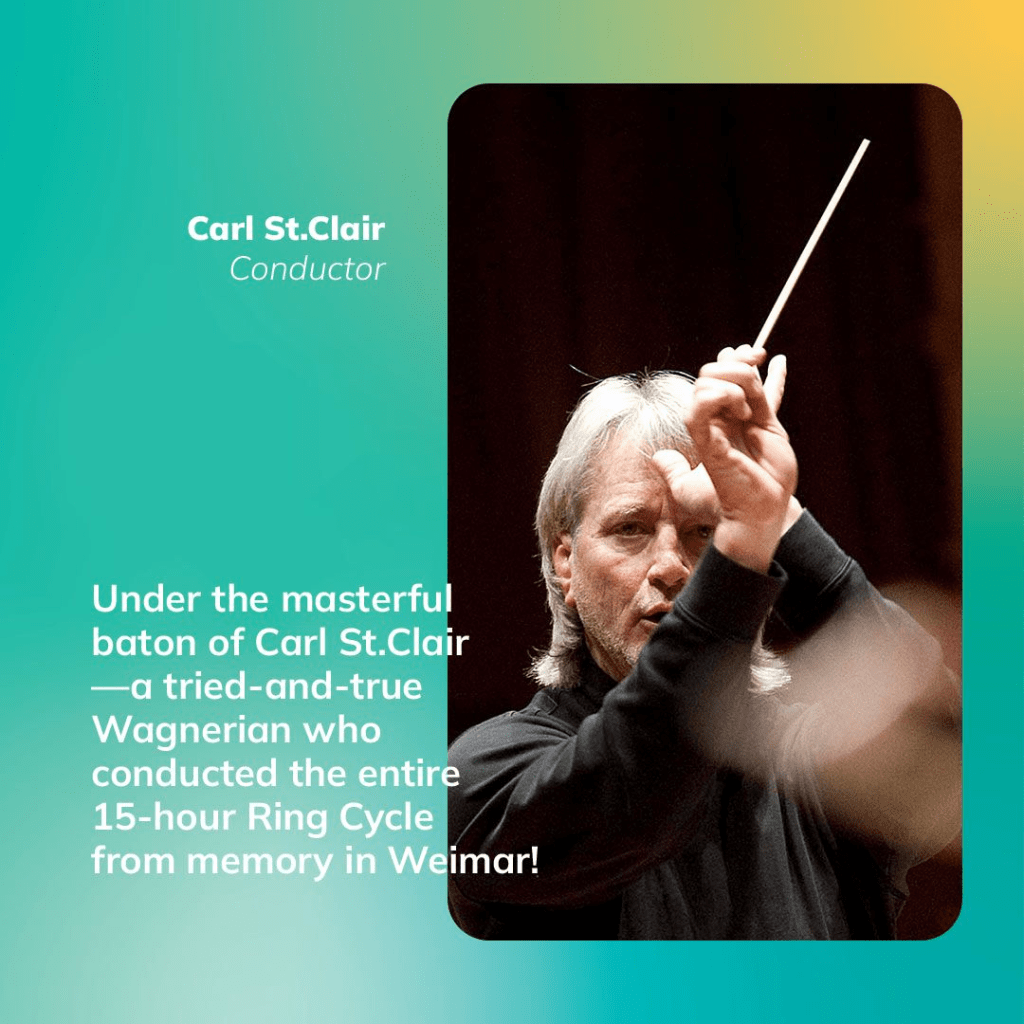

Pacific Symphony’s semi-staged production of Curse of the Ring: Das Rheingold takes place Apr. 10, 13, and 15. We encourage all ticket holders to attend a preview talk with KUSC Midday Host Alan Chapman at 7 p.m. for the April 10 and 15 productions and 1 p.m. for the April 13 production. The conversation will take place in the orchestra level of the auditorium.