“Scheherazade”: A Masterwork Inspired by 1,000 Stories—and a Heart Attack

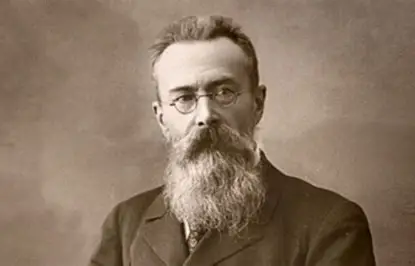

With such a plain spoken title, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (1888) has to be programmatic music, right? A retelling of stories from the Thousand and One Nights?

Well, yes…and no.

Richard Strauss, master of programmatic music, famously said “I could set a beer glass to music if I had to.” If you doubt it, listen to Till Eulenspiegel as Till mocks a group of stuffy academicians, or the sheep in Don Quixote. Strauss had a territory in mind and a highly detailed map.

Here, though, territory and map are emerging at the same time. Rimsky-Korsakov didn’t set out to tell these stories with precision. Yes, he was working with the materials of Orientalism already, but the stories serve as a very loose framework. The suite, one of the composer’s most popular works, is meant to be suggestive, not narrative. It evokes, not explains.

As Scheherazade herself might say, therein lies a tale.

This particular tale begins with a heart attack.

In February 1887, Rimsky-Korsakov’s close friend Alexander Borodin, a fellow member of Russia’s Mighty Five group of composers, was dancing at a ball when the congestive heart troubles he had suffered with for years struck their final blow.

At the time, Borodin had been working on his opera Prince Igor for close to 18 years. All along, Rimsky-Korsakov had been encouraging his friend to finish this ambitious work. Upon Borodin’s death he, along with another Mighty Fiver, Alexander Glazunov, took the task upon themselves.

Prince Igor is saturated in Orientalism, as were many of The Mighty Five’s works. Collectively, they were turning to Eastern influences to distinguish nationalist “Russian” music from Germanic and other Western traditions. Folk melodies from Central Asia, Eastern motifs, pentatonic scales and other similar compositional elements reigned, as heard in works like Balakirev’s blistering piano showpiece Islamey and Glinka’s opera Ruslan and Lyudmila.

It is while Rimsky-Korsakov was immersed in the exoticism of Prince Igor that he began to formulate ideas for his own voyage to the East. As for his commitment to the Thousand and One Nights as a conceptual framework, he was almost indifferent. At one point, the names of the suite’s four movements were: Prelude, Ballade, Adagio and Finale. Through the urging of his fellow composers, he relented and gave the movements the names by which they are known: I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship; II. The Story of the Kalendar Prince; III. The Young Prince and the Young Princess, and IV. Festival at Baghdad–The Sea–The Ship Breaks against a Cliff Surmounted by a Bronze Horseman.

The vague titles are a bit misleading, though. They don’t refer to any specific stories. They are meant to evoke, but not much more.

“In composing Scheherazade, I meant the hints [conveyed by the titles] to direct the listener’s fancy but slightly on the path which my own fancy had traveled,” said the composer. “All I had desired was that the listener, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairy-tale wonders…Why then, if that be the case, does the suite bear the name of Scheherazade? Because this name and the title The Arabian Nights connote in everybody’s mind the East and fairy-tale wonders.”

This, then, is a collage of sonic images ushering us into an imagined East. A fantasized Arabia of luxury and sensuality, of bazaars and magic lamps, The story of the Kalandar Prince? There are three such stories in the Thousand and One Nights, and no idea which (if any) the movement refers to. The Prince and the Princess? No specific story is identified, though the music’s romance and passion are clear enough.

The one unmistakable programmatic element is the narrative that ties these evocations together: the framing narrative of a sultan, convinced of the faithlessness of all women, who has vowed to put to death each of his wives after one night with them, and the beautiful Scheherazade, who delays her execution by telling him a series of fascinating tales. The original cliffhangers. We hear the menacing sultan in the first measures, and the enchanting Scheherazade in a filigree violin solo between movements, casting her spell over him, and us.

And while it is nearly impossible for some of us to separate out the music from the stories, it wasn’t so hard for the composer. In a later edition, he went back to his first impulse and did away with the titles.

SIX FAST FACTS

In terms of scale, Scheherazade is the composer’s largest orchestral work, though he wrote more than a dozen operas.

Alexander Borodin, whose Orientalism inspired Rimsky-Korsakov to write Scheherazade, was also a doctor, professor of chemistry, co-discoverer of organic chemistry’s Aldol Reaction, and founder of the School of Medicine for Women in Saint Petersburg. Underachiever.

Theater fans will be familiar with Borodin’s Eastern-influenced works, many of which were popularized in the musical Kismet.

Before turning his hand to composition, Rimsky-Korsakov studied at the St. Petersburg Naval Academy and served in the Imperial Russian Navy.

The music of Scheherazade has been used in several ballets, famously Michel Fokine’s production for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1910, featuring Vaslav Nijinsky. The composer’s widow Nadezhda was unimpressed, finding the orgiastic harem scene at odds with the work’s original spirit. To put it lightly.

Rimsky-Korsakov’s students included Igor Stravinsky, Anatoly Lyadov, Sergei Prokofiev, and Ottorino Respighi. Quite a legacy.

Experience Rimsky-Korsakov’s masterpiece live with Pacific Symphony under the direction of Alexander Shelley on Oct. 16-19 at Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa. Learn more