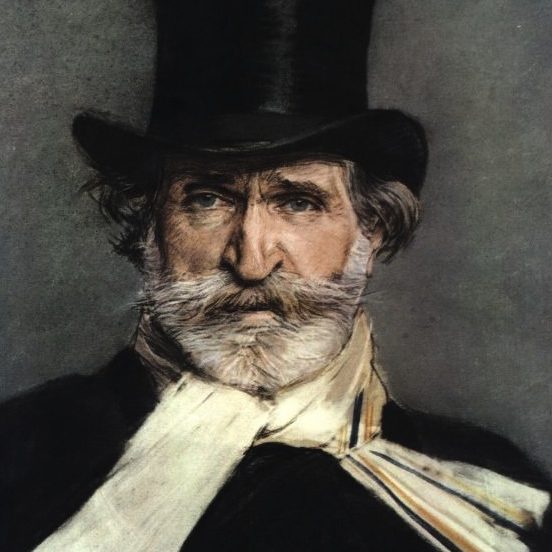

Verdi’s Mighty Requiem

Requiem Masses have long served as a way for nations to mourn their public figures. Cherubini’s 1817 Mass for Louis XVI and Berlioz’s 1837 Mass for those who died at the Battle of Algiers are two celebrated examples. The best known of course is Verdi’s Requiem Mass, but which public figure was it meant to honor? Therein lies a tale…

Verdi was inconsolable after Gioachino Rossini died on November 13, 1868. “A great name has disappeared from the world,” he wrote of Europe’s most famous opera composer. Four days later, he proposed a Requiem Mass to his publisher. Verdi’s vision for the work: it was to be a collaboration between Verdi and other Italian composers, each of whom would contribute individual movements.

His proposal came with a lot of stipulations, though. The Mass’s premiere had to be in Bologna, after the first performance the score would be placed in the Liceo Musicale and only brought out for Rossini’s anniversaries, and a committee would decide upon the composers, arrange the performance, and watch over the progress of the work.

You can see where this is heading.

The committee was formed and the work was completed (with Verdi providing the final movement, “Libera me”), but music by committee is not always the optimum way to proceed. The project was dogged by conflict, and came to an end when the head of the Bologna Teatro Communale refused to make his singers and orchestra available.

Verdi abandoned the idea and moved on. “[Completing the Mass] is a temptation that will pass like so many others,” he wrote to committee member Alberto Mazzucato. “I do not like useless things. There are so many, many Requiem Masses!!! It is useless to add one more.” The score for the “Libera me” was returned to Verdi on April 21, 1873.

A month later, Alessandro Manzoni died, arguably the one man for whom Verdi would resurrect his plans for a Mass.

At that time, few authors enjoyed the vast popularity of Alessandro Manzoni. The leading Italian writer of the Romantic age, he was read by his countrymen as fervently as Dante and was regarded by Verdi as a pillar of Italian culture. Verdi thought the author’s “I promessi sposi” was “not only the greatest book of our epoch, but one of the greatest ever to emerge from a human brain.”

Verdi did not attend any official ceremonies connected with Manzoni’s death, (“I would not have the heart to attend his funeral”) but ten days after Manzoni died, Verdi privately visited the author’s tomb, and came away with a desire to commemorate Manzoni with a Requiem.

He began work on the Mass in summer, 1873, while staying in Paris. He found great pleasure in composing the work, and by April he was done with what he called, one assumes with tongue-in-cheek, “that devil of a Mass.”

Verdi took an iconoclastic approach to the work. In general, Masses are rather malleable in form. Throughout ecclesiastical history, emphasis has been placed in successive eras on both rejoicing and grieving, on the glories of heaven and the terror of damnation. Verdi couldn’t help but invest his own unique experiences into the project.

“The text,” George Martin writes, “is ambiguous enough to allow musicians, by emphasizing this or that part or individual lines, to create a Mass that was primarily joyful or lamenting, majestic or simple, reflective or apocalyptic. Verdi, being a man of the theater, chose to make it drama.”

Explicitly dramatic settings for the Mass are uncommon, but for Verdi to write otherwise would be a gesture of insincerity on his part. Palestrina may have been one of Verdi’s heroes, but he wasn’t necessarily a model for his composition. One might think of the Requiem Mass as an oratorio, then, in Francis Toye’s words, a “sacred opera on the subject of the last judgement with Manzoni’s soul as the objective theme.”

There are four chances to experience this great work: Thursday-Saturday, June 5-7 as an evening concert and once more as a matinee on Sunday, June 8. Led by Carl St.Clair in his last concert as Music Director at the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall in Costa Mesa, Pacific Symphony will also be joined by four soloists and Pacific Chorale. Get your tickets today!

You can watch a clip of the “Dies irae” from the Metropolitan Opera below.