THE STORY BEHIND THE MUSIC: Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3

Pacific Symphony performs Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with Van Cliburn Gold Medalist Olga Kern this week, Feb. 1-4. The Feb. 1-3 evening concert is capped with Brahms’ First Symphony. The Sunday, Feb. 4 matinee performance solely features Rach III with additional commentary from Music Director Carl St.Clair as he guides you through the “Mount Everest” of piano concertos.

The 2023-24 Classical Series is presented by the Hal and Jeanette Segerstrom Family Foundation. All 2023-24 piano soloists are generously sponsored by the Michelle F. Rohé Fund. The Saturday, Feb. 3 evening concert is generously sponsored by the Board of Counselors. Media sponsors are The Park Club California, PBS SoCal, and Classical California KUSC.

You can learn more about the story below.

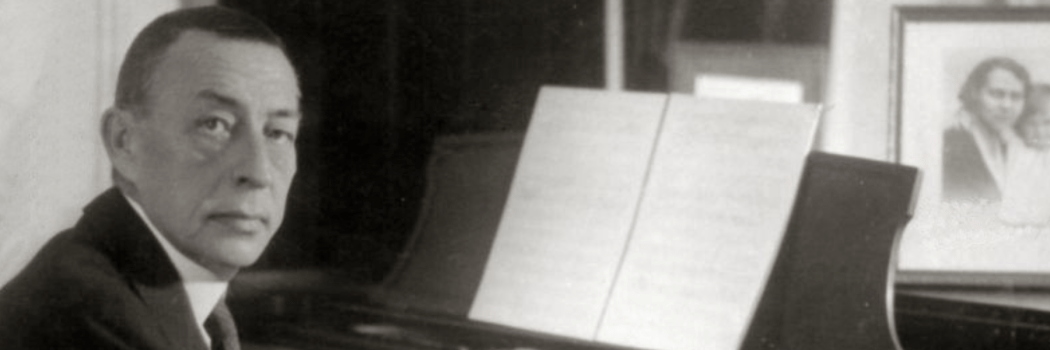

Sergei Rachmaninoff, the last of the great Russian Romantic composers, was also one of history’s great pianists—perhaps the greatest of all, according to some current re-evaluations. As a conservatory student in Moscow and St. Petersburg, he focused intensively on both piano technique and composition, and he was recognized as a great pianist throughout his career; just before his death, he was touring the U.S. as a piano soloist. Despite his latter-day moodiness and a bit of harmonic adventurism, you can hear that his style was rooted in the 1800s and in Russian tradition.

Listening to Rachmaninoff ’s long, brooding lines, their sweetness tinged with melancholy, it is surprising to learn that he died at his home in sunny Beverly Hills as recently as 1943. Another Russian expatriate composer, Igor Stravinsky, had come to the United States in 1939, became a naturalized U.S. citizen, and encouraged Rachmaninoff to move to Los Angeles. Once here, his hallmarks remained dazzling virtuosity and plush melody: Big intervals and big sound were natural parts of his musical vocabulary, and seemed to come naturally to his huge hands and long limbs. In fact, it is now believed that he had Marfan’s Syndrome, a congenital condition associated with these skeletal proportions. But if Marfan’s contributed to his heroic sound, there was a more delicate aspect to the Rachmaninoff style: fleet passagework, rhythmic pliancy, and long, singing lines. His third piano concerto is known to many pianists as Rach 3, or—thanks to Sylvester Stallone—as Rocky III.

The difficulties lie in Rachmaninoff’s unique combination of power, poetry, and speed. Those huge, complex chords, thundering octaves, cascading phrases, and purling legatos might be nearly impossible to play, but should sound effortless as they hold you in their thrall. It’s only afterwards, when you are released from their spell, that you might wonder how in the world the pianist played them with only two hands. Not surprisingly, this concerto is associated with some of the greatest pianists of the early 20th Century. Its dedicatee was the revered Josef Hoffmann, and though he never played it, it helped launch the career of an astounding newcomer named Vladimir Horowitz, who chose it for his graduation recital at the Kiev Conservatory and was soloist in the premiere recording.

The composer felt that his third concerto was more “comfortable” to perform than his second, but now, more than a century later, the third is considered more awesomely virtuosic. It was a spectacular showcase for Rachmaninoff’s particular gifts, and touring with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, he was both soloist and conductor in Chicago and Philadelphia; in New York he played the concerto with the New York Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Walter Damrosch, and with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Gustav Mahler.

Written in the three-movement form typical of Romantic concertos, the Piano Concerto No. 3 is replete with dazzle and plush melody. It begins with an allegro movement in D minor in which the opening statement, a simple melody, is juxtaposed against a slower theme. These frame a characteristic Rachmaninoff development section, with brilliant passagework and thundering climaxes that create intense drama before the original theme reappears in relative tranquility.

The concerto’s second movement, marked intermezzo, reveals what many listeners value most in Rachmaninoff: a melody of intense, swooning romanticism that goes wherever its organic, spontaneous development seems to lead it. Introspective in character, it builds gradually from quiet nostalgia to dramatic fortissimos that showcase the soloist’s power. This development is mediated by the reintroduction of the main melody from the first movement. Solo flourishes from the piano lead directly from its close. In a work that is both a sprint and a marathon, this movement provides the few moments of respite for the soloist.

Grace and speed are on order for the final movement, which builds toward a powerful climax by weaving together contrasting materials: accented march rhythms alternating with flowing, lyrical phrases. The movement reprises melodic materials from the concerto’s opening, concluding with a coda of thrilling power.

Michael Clive is a cultural reporter living in the Litchfield Hills of Connecticut. He is program annotator for Pacific Symphony and Louisiana Philharmonic, editor-in-chief for The Santa Fe Opera and editor of OperaHound.com.